The Day We Went To Auschwitz – by Gemma Lees

The approach to Auschwitz-Birkenau is almost disturbingly domestic and banal, blocks of flats with washing hung out on their balconies, huge fast food restaurant signs which can be seen from inside the camp itself, long lines of people from many different nationalities waiting for the toilets or sandwich vending machines and men in Hi-Viz jackets who show you where to park. And then you see that ubiquitous sign over its gates, one of the greatest and most cruel lies ever told, ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’ or ‘work makes you free’. The sign, made by forced labourers who placed the ’B’ upside down as a protest, was a promise by the Commandant of Auschwitz, Rudolf Höss, not that work would make its prisoners literally free, but rather that endless labour would give them a sort of spiritual freedom.

I had seen this sign in History textbooks my entire high school career and now I was walking underneath it with my son. I couldn’t help but think of the Roma and Sinti mothers whose entire families were deported to this awful place, simply because the Third Reich saw us as ‘racially inferior’. Dr Robert Ritter’s pseudo-science of ‘racial purity’ was utilised to persecute Gypsies based on a belief that we were naturally predisposed to inferiority and criminality. Facial features, bodily measurements and ancestry were used to segregate, deport, forcibly sterilise, incarcerate, experiment on and kill our people in the Porajmos or ‘Great Devouring’.

All visitors follow a guided tour along a pre-planned route taking in all areas of Auschwitz. Very few voices apart from the guides can be heard as the despair and horror of the place is palpable, every cobble, every wall, every doorway is saturated in it.

We were informed by a guide that decisions at the gates could take as little as a few seconds, anyone deemed not able to work would be immediately sent to the gas chambers in an act described by the Nazis not as murder, but as ‘extermination’, as we were seen not as people but as pests. We saw the rooms where prisoners were made to undress before being murdered as they were told that they were going to have a shower. In a move that added callousness to abject cruelty, some guards would amuse themselves by giving the condemned a towel.

We also saw the crematorium which was initially able to keep up with Auschwitz’s demands, as were the gas chambers, but not before long, victims were being shot in a courtyard and buried in mass graves dug by other prisoners. Walking through that courtyard was horrific. The whole point of the visit for me was to pay my respects and honour my ancestors but this area felt especially poignant and heartbreaking.

On display were some of the items confiscated from victims on entry to the camp, categorised behind glass cases, the sheer amount of each was shocking, especially when I thought of each individual or family that these items once meant something to. There were 40m3 of shoes in all sizes, almost 4000 suitcases, many with their owner’s names painted on the side and, as a disabled person who uses mobility aids, I was particularly shocked and distressed by the almost 500 prosthetic legs and arms, crutches and other essential mobility items which were taken from disabled people brought to Auschwitz to be murdered.

Another harrowing display concerned the hair of Auschwitz’s female victims, something which was stolen from them on entry to the camp. We saw thousands of plaits and there were tens of thousands more which had been turned into a closely-woven material used to make blankets and socks for German soldiers in a practise known as ‘human-recycling’.

I left Auschwitz feeling desperately sad but glad that I had made the trip and had shared it with my son. We can only prevent this scale of human depravity, this mechanised and bureaucratic mass-murder and this attempted erasure of our history and culture by keeping the past alive. By talking about the atrocities of World War Two suffered by our ancestors.

Another place where this takes place is the Memorial to the Sinti and Roma of Europe Murdered Under National Socialism which is in Berlin’s Tiergarten park near the Reichstag building.

You enter a clearing through a small gap in the bushes and all of the sounds of the park and its visitors seem to instantly melt away. All except a busker who covered the sound of a violin tone which is supposed to be heard with violin pop hits. The piece, ‘Mare Manuschenge’, composed, played and recorded by Romeo Franz is inspired by Sinti-Jazz and Sinti-Swing.

In the clearing there is a large circular pool which is lined with steel, so it perfectly reflects all of its visitors, the surrounding trees and the Reichstag. It is almost unnervingly still, with an odd stray leaf providing its only ripples. In the centre is an elevated black triangle, representative of the uniform badges that Gypsy concentration camp prisoners wore. At lunchtime every day, it retracts and reappears with a fresh flower.

Roughly broken stone slabs which symbolise the lives which were demolished are embedded in the ground around the pond. Engraved into them are the names of the 69 places where concentration camps which targeted Roma and Sinti victims stood or where mass executions of our people took place. ‘Auschwitz’, a poem written by Italian Roma Santino Spinelli, circles the pond in English, German and two dialects of Romanes.

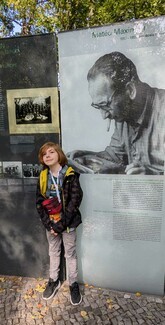

Coming back out of the clearing, I was able to experience the open-air exhibition, which contains a very special link to my history. Added in 2022, it depicts the biographies of nine persecuted or murdered Roma and Sinti people, with stories of resistance and the struggle for recognition for the treatment of Gypsies by the Nazis. My Dad, storyteller and children’s author, Richard O’Neill, wrote the biography of Matéo Maximoff, the first well-known French Romani author, a storyteller who wrote books based on the Romani oral storytelling tradition and fought to keep the Romani language alive. As my son and I stood reading my Dad’s words, our family history and the history of the creativity that exists in all three generations felt truly powerful and meaningful.

Rather than the abject horror of Auschwitz, the memorial felt more like a place to reflect and to celebrate the people and the culture that survived. It felt less alien to slip back into modernity, into a bustling capital city after our visit. It felt like a place that I would visit regularly if I lived in Berlin, to refresh and renew my respect, my love, my pride and my hope as a Romany Gypsy woman, daughter and mother, just like the new flower that appears every midday.

Photographs and words by Gemma Lees for the Travellers’ Times