Debut novel shines light on removal of Gypsy-Traveller children

Mark Baillie explains how his novel 'Salvage' delves into a tragic but little-known aspect of Gypsy-Traveller history

In spring 2021, I had a much-anticipated phone call with the researcher and genealogist Robert Dawson.

I own a number of Dawson’s books on the history of Gypsy-Travellers in Britain and had contacted him to ask if I could speak to him about the novel I was writing.

Unfortunately, the conversation didn’t go as hoped.

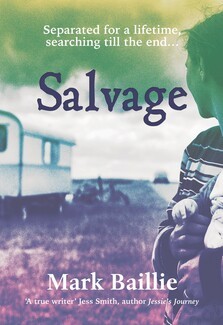

After I explained the novel was set in the 1980s and about the search for a young Traveller girl removed by authorities 55 years earlier, Dawson’s view was that such an attempt would have had virtually no chance of success.

He explained that authorities often took Traveller children with little forewarning or justification and that, before the introduction of the Adoption of Children (Scotland) Act 1930, such removals didn’t need to be documented.

This felt like terminal news for my novel, which at that stage I’d been working on for a year. I’m glad I didn’t give up. The theme of a seemingly hopeless search and what might drive a person on such a Quixotic quest became the story’s beating heart.

Two years later, after finishing Salvage, I learned of the ‘Tinker Experiments’ campaign for a government apology for the historic treatment of Gypsy-Traveller families, which includes the removal of children.

I’ve met some of those involved in the campaign, heard their stories, and seen depressing evidence.

Sadly, none of it was news to me. Pick up any book on the history of Gypsy-Travellers and you’ll soon come across laws and policies designed for their assimilation into ‘mainstream society’.

An early example is the 1574 Act for the ‘staunching’ of Gypsies (among other ‘strong beggars and vagabonds’), setting out that their children could be taken into servitude by subjects of the realm of ‘honest estate’.

A few centuries later, the Quaker John Hoyland believed it was worth ‘communicating the benefits’ to Gypsy-Traveller parents of placing their children with non-traveller families for education.

Here are Hoyland’s musings in his 1816 publication Historical Survey of The Gypsies: ‘Their [children] being placed among a much greater number of children and those of settled, and in some degree of civilised habits, would greatly facilitate the training of Gypsies to salutary discipline and subordination; and the association it provided for them out of school hours, being under the superintendence of a regular family, would, in an especial manner, be favourable to their domestication.’

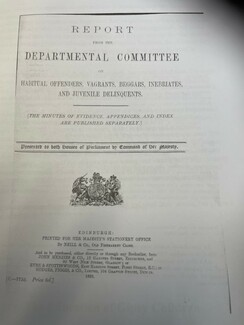

Finally, let’s go to the 1895 government Report on Habitual Offenders, Vagrants, Beggars, Inebriates and Juvenile Delinquents. Officials speaking to the inquiry about the need for education among Traveller children in Perthshire were clear the solution was forced placement in industrial schools.

It’s difficult to be sure of the exact number of children removed when a combination of methods were used, involving different organisations, and stretching over centuries. In some cases, boys over a certain age were sent into the navy and girls sent to be servants. Some were placed in industrial schools, and there is evidence of children being sent to Canada. Before the abolition of slavery, there are records of Gypsy-Travellers being transported to the Caribbean. So it’s not surprising that some estimates put the total figure of taken children into the thousands.

That Salvage is being published the same year the government’s findings on the ‘Tinker Experiments’ are expected is sheer coincidence, but I hope it helps shine a light on this tragic aspect of Gypsy-Traveller history.

Salvage is published by Tippermuir Books http://tippermuirbooks.co.uk

By Mark Baillie

(Lead photo of Mark Baillie with a copy of Salvage, courtesy of Mark Baillie)