“no one never asked”

It is the beginning of November, I am calling my grandmother to let her know that I will be visiting Poland soon, and I would like to interview her about the past. She is reluctant. I am trying to explain to an older Roma woman Holocaust Memorial Day and its importance. She doesn`t understand. “Why would someone be interested in Romas and what has happened to us?” she says. I knew I needed to change my approach. I couldn't use the word interview anymore. “I would just like to talk to you a little bit about travelling in caravans, life back then, how you met grandad”. I couldn't see her but I knew she was smiling then. She still misses him.

You pay – she says laughing?

I am broke.

I’ll see you in a few weeks son.

The Roma do not like talking about the Second World War. It is almost taboo. Not many of them are familiar with words such as Holocaust or Samudaripen (a word Roma intellectuals came up with). These words are used in the non-Roma world. Amongst themselves, if they talk about the War they usually say, “during Hitlers time” or “during baro mariben – the big fight”. But they don’t talk about it very often.

Between 1933 and 1945 Roma in Europe were targets of Nazi persecution. The Nazi regime viewed Roma as “asocials.” During World War II, the Nazis and their collaborators killed between 250 thousand and 2 million of European Roma. The discrepancy between the numbers quoted is so great because, it is impossible to know the exact number of Roma population before the outbreak of the war.

Roma were not only killed in the concentration camps. Roma men, women and children were killed inn their caravan camps, in the forests. Whole communities, families were murdered. No witnesses, silently. Forgotten.

A few weeks later I am sitting in front of my grandmother. The tea is as always; way too strong and very sweet.

Why do you want to talk about the past? she cannot believe someone would be interested in what an older Roma woman has to say. Has anyone ever been interested in us – she adds.

I am starting with a very simple question: what is your name? Sabina Rybicka. How about your Roma name? – Incioro. Yes, Roma have two names. Official for admin purpose. That’s a name for the non-Roma world and Roma name. The one they are attached to more.

How old are you? She laughs a bit. Not because you shouldn’t ask a woman about her age but because she simply doesn’t know. “I am old but I do not know how old I am” She was born in a caravan camp. Somewhere in woodlands. Somewhere in Poland. It must have been before the war and she was told that it was around harvest time. Like many Romas, she never went to school. She says that life was the best education although sometimes you need to repeat “ a lesson” a few times before you learn it.

Tell me something about the past, something you remember – I ask her.

I had a big family. A lot of siblings, uncles, aunties. Our camp was made of over fifty caravans.

We travelled from spring to autumn. From one place to another across Poland. We would rent a house during winter from the Poles, but once it was getting warmer, we were on the road again. Before The war, my dad was a horse trader. He was very well known and respected. Our caravan was stunning. It had floral paintings all over it and wooden dragon statues; you know; to protect us from bad luck. I remember us kids playing in the forest. Women would take care of their families. They would cook, and do laundry in the river. A lot of women were fortune-tellers. They told fortune to the Poles, not for money, but for some food. Evenings were the most beautiful. A lot of singing and dancing around the bonfire. Older people told stories about ghosts and old fairytales. We kids would sit and listen, eating together from one plate. Then everything changed. She is silent for few minutes.

We were captured in the forest. My whole family. That one day changed everything. I was a little girl and I did not understand what was happening but I knew that there was something bad going on.

It is dark. The air is heavy. It has to be like that when a lot of people are stuck for days in a closed train carriage. The stench of sweat, faeces and fear. There is no air. People are dying. I am scared. Someone told us that we are being sent to Russia, Sibir. I didn’t know what it means but soon I was to find out that.

The first thing that comes to my mind when I think about that time is hunger. That and cold. I cannot remember how long we were there. Days turned into weeks and months. Maybe years? Every day looked almost the same. You just get used to it. Apart from one thing; your relatives dying or being killed. One never can get used to that.

We had to work very hard for no money. Maybe the remuneration was staying alive? Men worked the hardest. Physical work in the forest. Sometimes we would get some food but that was not every day. Women had to work as well. My mother did not have shoes. Her feet froze and eventually had to be amputated. Sometimes I would sneak out of the camp, which was not heavily guarded and go to a village and beg for some bread. We all learnt new words: tuberculosis, scarlatina, dysenteric, typhus.

I can see she is getting tired. There are things she doesn’t want to talk about.

She stands up and goes to a wardrobe. After a few minutes, she comes back with a little bag wrapped in a white kitchen towel.

We managed to come back to Poland. Those of us who still were alive. It was still the war. We were hiding in forests. Our caravans were not anymore colourful or big. We did not want to be visible. Instead of fifty caravans now there were just a few. It felt lonely.

Your grandfather Ludwik`s tribe was still travelling around this time. From what I know – it was a pretty big camp. Around sixty people They just arrived at a new place. His father at this time was in Auschwitz. Ludwik was sent by his mother to a neighbouring village just to see what was there. When he was about to come back to the caravan camp, some Poles stopped him and said not to go there because the Nazi ambushed the caravan camp. He tried to run away but they forced him not to go. When eventually he got there, the whole caravan camp had been murdered. His mother, his siblings – everyone. All killed by the Nazi. The Poles were burying them.

He said once that the air had a scent of death.

Many years later he tried to go back there. To pay his respect. Sometimes we would get close, but then he would stop and say: I cannot do it. He never went there.

My family was still hiding but we were captured again.

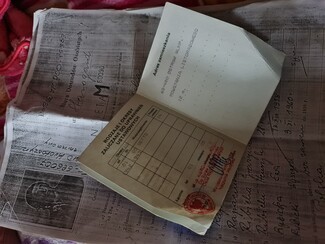

My grandmother then started to unwrap the little package, in the white kitchen towel, that she had retrieved from the wardrobe earlier. Inside the bag is some old documentation.

This is my ghetto ID. I have no words to describe how it was there. Again hunger, biting up. People dying all around. One loses hope. A lot of people tried to escape. Some succeeded but those who were caught were killed straight away. Two of my sisters died in the ghetto. A lot of my family members died there as well, and in concentration camps. Some of us survived.

There were no Roma witnesses at the Nuremberg Trials.

Only in late 1979 did the West German Federal Parliament identify the Nazi persecution of Roma as being racially motivated, creating eligibility for most Roma to apply for compensation for their suffering and loss under the Nazi regime. By this time, many of those who became eligible had already died.

Have you ever spoken about that gran?

No, no one ever asked.

By Szymon Glowacki

Szymon Glowacki (he/him) is the Stronger Communities Outreach Lead at Protection Approaches – a charity working to prevent identity-based violence in the UK and worldwide. Szymon develops, delivers, and leads workshops with communities and schools, including Protection Approaches’ annual Holocaust Memorial Day workshops with students across London. Szymon has worked for the past 10 years with Roma-Gypsy communities in Poland and the UK, and was himself born and raised in Poland to a traditional Roma-Gypsy family. Learn more about Szymon’s work on twitter at @IBVprev.