“tinkers and gipsies” – the historic tragedy of the attempted eradication of Scotland’s Travellers

“There are some really tragic stories. The one I am speaking about is from 1907 and I keep going back to it is because it was so tragic. What happened was the wife drowned in an accident and she left her husband with ten children. They were under constant supervision from the state with people visiting, and all these threats and things. The man eventually committed suicide and then all the children were taken and sent to the industrial schools and then on to Canada and Australia. This policy was still in operation in the 1950’s. There are a lot of people who grew up in these industrial schools and never knew they were Travellers – they were completely denied their culture and their family. A lot of them grew up with mental health difficulties and a lot of them committed suicide.”

The Travellers’ Times is talking to Scottish Traveller campaigner David Donaldson about the historic forced removal of Scottish Traveller children by religious institutions, acting with the collusion of the government, between the early 1900’s and the 1960’s. This is the second part of our investigation into the forced adoption and migration of Gypsy and Traveller children. Donaldson says the key to unlocking the tragedy that his people had to endure – the ripping away of children from their parents and families – is an 1895 government report into “habitual offenders, vagrants and inebriants in Scotland.” Donaldson believes that this report shaped how the authorities treated Scottish Travellers from the day it was published to over half a century later – and that there are even echoes today of this official culture and policy that underpinned the governments attempt to eradicate Scottish Traveller culture by taking Traveller children, ‘re-educating’ them, and wiping clean their identity. Donaldson says that much of this history is hidden from non-Travellers, yet is crucial for understanding his people's culture today.

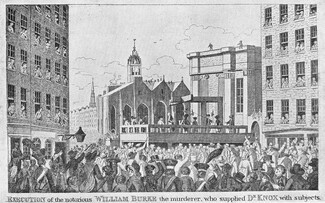

One example of this hidden history are the stories Scottish Travellers tell of “the Burkers”, says Donaldson. The Burkers where body-snatchers with a difference. Like William Burke and William Hare, the infamous Scottish pair who sold bodies to the universities to further the boundaries of knowledge in medical science, the Burkers where people who did not wait till the bodies they sold where dead and buried in the graveyard. Instead the Burkers murdered their victims and saved themselves the spade-work. Unlike William Burke, who was caught by the authorities and ended his life on the gallows in Edinburgh on a January morning in 1829, the Burkers continued their murderous activities, particularly against Scottish Travellers, right up until the 1940’s. “The Burkers where a big thing for us,” says Donaldson. “In the late 1800's they would dig up bodies but that became more difficult, so what they would do is they would go and specifically target Travellers and people walking the roads because in some sense no-one would miss them. So we have got hundreds of stories about Burkers but they are not old; I mean some country people have stories, isolated cases, but they are all from the Eighteen Hundreds, but my great-uncle, who is still alive, had to run through a field because him and his parents – my Great-Granny and Grandad – where getting chased by Burkers when they were camped out. And they were going to kill them if they caught them. And that was in the 1940’s. The forced migration story is very similar to the Burkers in that I think Travellers think that country-folk (non-Travellers) know about it, but they don’t and its so important in a broader context – not just to realise what happened to our community historically - but to actually realise the impact it has had on our community and how that plays out today.”

The 700 page report based on a government inquiry, that Donaldson says is the key to understanding how the authorities treated Scottish Travellers, was intended to “call attention to habitual offenders, vagrants and inebriants in Scotland”. The report was presented to Parliament in Westminster in 1895 by its author, the Secretary of State for Scotland Sir George Trevelyan. One “class” of people that the report scrutinised, distinct from “habitual offenders, vagrants and inebriants”, but still seen as a related problem class by the report’s authors, were “tinkers and gypsies”. The most understandable and authoritative account of this key report is the book ‘Empty Lands: Aspects of Scottish Traveller Survival’ by Robert Dawson (2007). For Dawson there are four reasons that the report is important; the first is because it shows how ‘tinkers and gypsies’ were perceived at the time; the second because of the engravings of Scottish Travellers and their camps that it includes; the third because it contains the 1893 census of Scottish Travellers and Gypsies and finally – and this is also why the report is important for Donaldson - because of what happened to Scottish Travellers as a result of the reports publication – and the effects that this still has today.

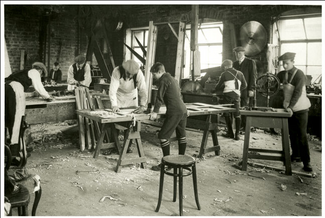

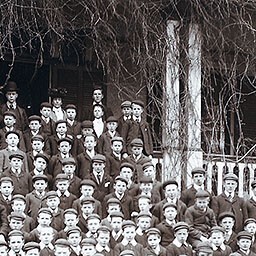

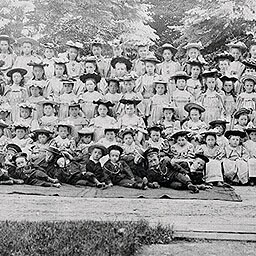

The 1895 report committee, made up of government and public officials, mostly met and heard evidence in Aberdeen, Glasgow, Edinburgh and London and their remit was not just to enquire into the ‘problem’ – it was to come up with solutions for the problem as well. Sir George Trevelyan writes in the report’s introduction that their intent was to “suggest such remedies as may, while deterrent, be likely to bring about their reformation.” The committee heard much evidence from the officials who served as witnesses – no Travellers where called to testify - that suggested to them that as adult “tinkers and gipsies” were largely beyond reformation, efforts needed to be concentrated on the saving of the children. For this to succeed, the report concluded, the children would need to be removed from their families. The authorities did not need any more encouragement. Using a few policy changes suggested in the report as to how hostels, work houses, and cases of neglect and cruelty were funded, Dawson says that the report “was used (by the authorities) as the pretext for rounding up Scottish Traveller children over the age of seven, and transporting them as household and farm servants to Australia and Canada.”

“It was basically the church working with the government,” says Donaldson. “It all came out of the 1895 report. It was happening before then but it wasn’t policy. In the 1895 report the decision that came out of it was to start taking children off Tinkers that continued to live the itinerant lifestyle and it was backed up by the church and the government. The church founded a lot of the institutions abroad, and it propagated a lot of the rural detention centres, like the Quarriers, where the children were kept before they were sent away. A lot of kids where taken for little or no reason. I have examples from my own family. It’s such a huge issue and after talking to so many country-people about Traveller history, I’ve come to realise that as a community we are very ignorant about country-folk understanding. I was always brought up believing that the settled community knew just as much as us about the forced adoptions, the forced migration and the Burkers actually chasing Scottish Travellers down right up until the 1940’s and 1950’s, and they don’t - it’s completely unknown.”

Quarrier Homes still exists as a charity today. In their own words, they state on their website that they were founded by William Quarrier, a successful Glasgow shoe retailer, who began caring for orphaned and destitute children in Glasgow in the early 1870s. He, himself, had experienced a very impoverished childhood, a situation, say the Quarriers, which he overcame through “hard work, determination and Christian faith”. Realising large institutional orphanages offered little in the way of a home environment to children in their care, Quarrier determined from an early age to set up a children’s village, where poor children from the towns and cities of Scotland might enjoy a new life in cottage homes, under the supervision of house fathers and house mothers. With the support of a growing band of committed supporters, Quarrier was able to purchase land at Bridge of Weir, Renfrewshire, some 15 miles south west of Glasgow, and began to set up the Orphan Homes of Scotland (now Quarriers). What the Quarriers website doesn’t tell us is that the Bridge of Weir was at the centre of a child abuse scandal that hit the news in 2010 and that they were excoriated by two very recent inquiries into forced migration and child abuse – one by the UK Government and one by the Scottish Government.

Behind the official history of the Quarriers faith-inspired good works lay a darker truth, which was revealed in both the Scottish and the London based inquiries into child migration schemes. Over 4,000 children were taken from their families and sent abroad from the UK from 1946 to 1970, to countries such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada, says the report by the UK Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse. The report, which includes the stories of surviving victims, goes on to say that many of these children suffered appalling abuse – including horrific sexual abuse - at many of the care homes, religious institutions and foster families they were sent to. An estimated 2,000 of those child victims are still alive and some of them gave evidence to the inquiry. Many other children were forcibly migrated in the decades before the Second World War, with the majority – 90,000 - being shipped to Canada. Many of the children were sent to work houses, farms and factories run by ‘voluntary’ organisations who were meant to protect the children and some were ‘fostered’ to individual families. Voluntary societies such as Barnardo’s, the National Children’s Home (NCH), the Church of England Waifs and Strays Society and the Fairbridge Society, as well as the Quarrier Homes, also became involved, as did the Catholic Church and the Christian Brothers. Evidence given to the Scottish Inquiry showed that from the late 1800’s to the start of the Second World War, 30,000 children passed through Quarrier homes alone and 7,000 were sent to Canada. It is not recorded how many of these ‘destitute and orphaned’ children taken and sent abroad where Scottish Traveller children.

“That Traveller lifestyle was detrimental to a child’s development was social work policy for a long time,” says Donaldson. “So the common practice was to just take them away and put them in hostels and homes and then ship them out abroad. A lot of people weren’t sent away but they were taken to orphanages and industrial schools and it was for the reason that social workers deemed that there was an inherent risk factor with the lifestyle.” Donaldson says that this idea of an inherent risk in Traveller lifestyle” has echoes within attitudes held by social work professionals today, and that on top of that his people’s historical memory of state child snatching impacts on how many Travellers engage with social work professionals. This claim by Donaldson is backed up by research from Dan Allen and Sarah Riding, social work lecturers at the University of Salford. Their study found that child protection professionals working with Gypsy, Roma or Traveller (children are “generally ill-equipped and under pressure” and there was evidence of automatic prejudice that presupposes risk. More than half of the 137 child protection professionals surveyed by Allen and Riding believed GRT children to be at more risk of significant harm than any other child, and just over half of those said the reason for this was “family culture”. One social worker said their work with Traveller families is “characterised by professional suspicion and assumptions”. Much of those assumptions and suspicions can be seen in the testimonies of witnesses to the 1895 report committee. For every official witness who seems to have made some human contact with Scottish Travellers, who argues that they perform a useful role in agriculture, have a high set of moral standards and work ethic and take care of and love their children within the context of their own culture, there are many more who characterise them as lazy, drunken, dirty and feckless and de-facto child abusers because they do not send their children to the school – which at the time were the same limited, highly religious and severe primary schools that the settled labouring class sent their children to.

Donaldson says both himself, and fellow Scottish Traveller campaigner, author and historian Jess Smith, has access to “hundreds” of personal eye-witness accounts of Traveller children being taken and put into institutions by quasi-religious organisations and state social work officials, but he is worried that this vital living memory element of his people’s history will fade as time marches on. He believes these accounts need to be recorded before the bearers of Scotland’s tragic history of the persecution and attempted eradication of its nomadic indigenous ethnic minority pass away. “My ancestors where McPhees from up north and around 1905, they were both convicted and sent to prison in Dingwall, because their baby had died and they were charged with child neglect and abuse,” says Donaldson. “What was wrong was that they were camped in a cave and that classified them as child abusers and they were actually sent to jail for it. Just after losing their baby and because they were then sent to jail, a load of their other children were taken by the Quarriers and they were sent to Canada.”

To be continued…

By Mike Doherty/TT

(Lead picture: Scottish Travellers by Loch Eriboll ©National Trust Images/Edward Chambré Hardman Collection)