“Leaves on the wind” - Welsh Kale campaigner and elder Bob Lovell

“Kushti Divvus T T , Shom Bob Lovell ta man av kata Nevo Zeatem , Man av kata Nevo Zeatem pardel Ki O Puri Tem Wales , oprey O Sasta Chiriclo , Ame Romani sar Patrania oprey o Baval and Ando Butti Temeskri Ame sar charos Welsh Kale”

“Hello Travellers’ Times, I’m Bob Lovell and I come from New Zealand, I come from New Zealand over to the Old country Wales on an Aeroplane, we Romani are leaves on the wind (and) in many countries, (yet) we are always Welsh Kale.”

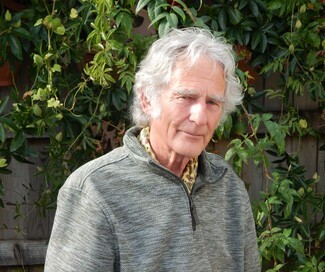

Bob Lovell, 73, a campaigner for Romani rights, an award-winning folk singer and a sailor, is the first of his Romany Gypsy family to be born in New Zealand after his Welsh Kale father, Adolphus Lovell, who was in the Merchant Marine at the time, emigrated there shortly after the end of the Second World War. In September, earlier this year, Bob Lovell was visiting Wales and staying at his cousin Allison Hulmes’ home in Swansea for a few weeks to take part in a project to work with the Welsh Government to include the Welsh Romanus dialect, of which Bob Lovell is a fluent speaker, into the Welsh school curriculum.

As Bob Lovell and I eat cake and drink our tea at a table in the garden, Allison Hulmes tells me about the project. “What was really lovely was we were in primary school in Newport in South Wales a couple of weeks ago, and this school is in an area where our family were moved into slum housing after they cleared the stopping places in the post-war period,” says Allison Hulmes. “So, it was something really like going full circle and taking the Welsh Romanus dialect into the school.” Bob Lovell agrees and points out that some of the schoolchildren of Indian descent, as well as some of the Romany Gypsy children, already knew some of the words. “Del (sky) - Kam (sun )- Choon (moon )- Varst (hand) Mui (face )- Heart (Zi ) - Knok (nose) - Pindo (foot) - Angosh -(Toenail ),” it’s the same root words in Romani and Hindu,” says Bob Lovell. However, the project is, as they say, another story and I am in Swansea for a rare chance to interview a prominent Romany Gypsy elder and campaigner about his life.

This is not Bob Lovell’s first visit to Wales. As his “dadus” Adolphus Lovell lay dying in 1997, Bob Lovell promised him that he would return to Wales to find and contact his relatives. “The first time I came over was in 1999 and I was searching for Allison’s mum and her sisters,” says Bob Lovell. My dadus, when he was dying, wanted me to find them. We are Romany folk and we lost contact because of the lack of the old folks being able to read and write.”

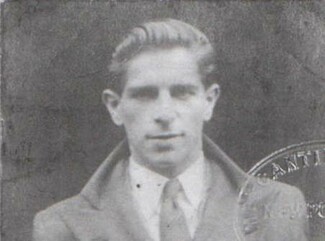

Bob’s father emigrated from Wales to New Zealand in 1947. Adolphus Lovell already had a taste for seeing the world through his service in the Merchant Marine, and he could also see which way the wind was blowing for the traditional Romany way of life ‘on the drom’ (on the road) back in the ‘old country’ Wales. As Adolphus Lovell was starting a new life in New Zealand, on the other side of the world, in Newport, south Wales, the authorities were continuing with a crackdown on the traditional Romany way of life, using the tools of assimilation; including forced settlement from the camps into slum housing, and forcibly taking Romany children into the care of social services. What happened to the Lovells in south Wales, an act of state violence that Allison Hulmes – whose mother and aunts were taken into care as a babies during that time - calls “the rupturing,” was being repeated up and down the UK from the highlands of Scotland to Lands’ End in Cornwall as the life on the drom and the old Gypsy and Traveller way of life was eradicated or severely curtailed and marginalised by the authorities. That many Romany men were away fighting the Nazis didn’t seem to have any bearing on what the authorities did – in fact it made their campaign of forced assimilation easier.

“In Newport they came and took my cousins, they were in a bender tent, and because a lot of the men had gone away to fight, they took the horses off them, so they couldn’t travel,” says Bob Lovell. My gran and the women were looking after the chavvi (children) and these buggers came in and took them and said they were not being looked after properly, while the men, like my father and his father before him, were fighting for their country and for freedom.”

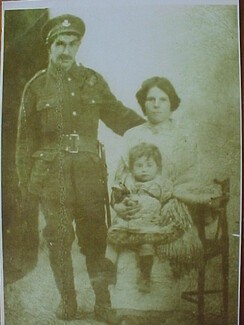

Adolphus Lovell’s father – also named Adolphus Lovell – had fought in the First World War in a special mounted reconnaissance unit until he was wounded and gassed and invalided out by wounds, explains Bob Lovell. Adolphus Lovell senior died in 1945 as the Lovell family camp was dispersed by the authorities, with Bob Lovell’s father de-mobbing in New Zealand, where he had spent time on leave, for a fresh start. “My father being the oldest boy, or one of the oldest boys, he had to provide for the family,” says Bob Lovell. “He was in the Atlantic convoys to Russia. Twice he was on ships that where torpedoed and he survived. But he stayed at sea because he is providing for the family, for all of them,” he adds.

“My father eventually came to New Zealand and he really loved it and he knew that things were never going to be the same in the old country because the old life had gone. He was bought up on the drom; the old way, travelling all about,” says Bob Lovell. “He was bare foot until he was twelve. He used to have to look after up to 20 pit ponies that granddad would get for next to nothing, and then bring them back to health while they were traveling. It was a hard life, nothing romantic about it, but he knew that he wanted a better life for his children. I was the first born in New Zealand. My sisters come a lot later and they got well educated. I didn’t get well educated; I hated school, I am probably the crossover between the old and the new,” he laughs.

“At first, my dadus always said we'd come back. But then he met my mother, Rona, and she was descended from Scottish migrants to New Zealand and they came in the late 1800, early 1900 to New Zealand. They were Scottish Travellers originally. I've got Whites, Harris, Stewarts, Mason and a couple of others that I don't recall on that side of the family.”

Bob Lovells’s father stayed and settled down and started making a living; sometimes travelling around servicing industrial and agricultural machinery, and sometimes working with horses on the farms. He did well and thrived, creating a new life for his new family, yet all that time Adolphus Lovell also kept in touch with the old ways, including his Welsh Kale language; the Welsh Romanus dialect, which he spoke fluently, and his memories of the old way of life and of his Romnipen (family and kin), even as he lost contact with his old family back in Wales. Eventually, as Adolphus Lovell got older, Bob Lovell came to realise that the responsibility of keeping Welsh Romanus dialect alive – which is an oral language and not a written one - was going to become his responsibility, alongside the responsibility of fulfilling his father’s dying wish and tracking down the Lovells still living back in Wales. “He knew the name of all the birds, you know, he could speak proper sentences that made sense about everyday things, but he wouldn't let me record him,” says Bob Lovell of his father. “He wouldn’t let me record him even as he lay dying in 1997,” adds Bob Lovell. “So, I started to write it down instead.”

As young man Bob Lovell was a regular on the New Zealand folk music circuit, and so he also started to introduce the Welsh Romanus dialect into his songs. “I used to do folk gigs and I played on in New Zealand and in Australia, but not big-time stuff,” says Bob Lovell. “Usually, the biggest audience might be 3,000 people, but generally in a folk club it's a couple of hundred. There's no real money in it, but I used to love it once. I was a bit shy about doing my Romanus stuff for a long time, but I decided that when my father was dying, I had to. And I'd get stupid remarks. People come up to me and say ‘you can't be a proper Gypsy, you weren’t born in one of those painted caravans,’” he adds. “I've written a lot of songs, or rather I don't actually write them, instead I'll have a dream or I'll wake up in the middle of the night and I'll have a riff going through on the guitar or some words, and I’ll record it on a simple device and then my wife Jane will actually write the lyrics down,” says Bob Lovell. “I used to do a lot of political songs back home about New Zealand politics, like the poor being treated worse and the corporates and privatization and all that. And that's how I won an award.”

After Adolphus Lovell died, and before Bob and his wife Jayne Lovell left for the UK, a friend wrote to a Welsh newspaper asking about the Lovell’s relatives. The published letter received many replies from “gorja folk,” including a reply from someone claiming to have recently seen Bob Lovell’s aunt – his father’s youngest sister – alive and well and shopping in the market in Newport, south Wales. “So that’s how I found out where they were,” says Bob Lovell. “I knew they were here in south Wales. So, myself and Jayne flew over and then brought a van to live in once we got here, and we travelled for about eight months. We would travel most days from one place to the next, seeing family and other Romany friends I had got to know.” After the eight months were up, Bob and Jane Lovell sold the van at a regular park up for van-dwellers near Clapham Common, London, and flew back home to New Zealand.

As the Vice-Chair of the Australasian Romani Association, Bob Lovell has been involved in many New Zealand-based campaigns for Romani and Roma rights. One of these involved educating people about the misappropriation of Romany Gypsy culture, language and identity by New Zealand’s van and truck dwelling community and the misappropriation of the word ‘Gypsy’ by commercial enterprises; The Gypsy Extravaganza and the Original Gypsy Fair, that run the popular and touristy summer markets and fairs where the van-dwelling community sell their wares.

Bob Lovell approached the people running the Gypsy Extravaganza to try to persuade them to stop appropriating the word ‘Gypsy’ and after listening to him they agreed to stop using the word ‘Gypsy’ in their name. “The Extravaganza were good, decent people, younger than the other lot who run the Original Gypsy Fair,” says Bob Lovell. “They were young people, lots of rings and things, but decent, educated people. I went and talked to them in person, about 40, 50 of them all around me and some of them were a bit hostile at first. And I said to the lady that managed it all, we're not trying to close you down, you've got every right to go around the country in the summer making a living like that, but please don't use Gypsy with a capital G, because you're not Gypsies. As an ethnic people, that term has been used for us for 900 or something years. You just can't just come hopping along and say, ‘oh, you're going to be a Gypsy because of your lifestyle’ because it's not about lifestyle.”

Bob Lovell explains that portraying the traditional Romani way of life as a romantic wanderlust can be offensive – because that was not what the real life on the drom was like. “I told them that the real original Gypsies didn’t bloody wander around for no reason; they travelled firstly, because of their trades and the secondly, the more important reason, because of the prejudice,” he explains. “They didn’t choose to move; they were forced to move. Bob Lovell then breaks into the Welsh Romanus dialect: “Butti Romani komesa ki Artch ando yeck tan , ta suttlo ando O kushti tatto wudrus , O grai oprey o pov abrie O tan ta jal abrie ker booty oprey O pov.” (English translation: Many Romany desire to stay in one place and sleep in a warm bed, a horse on the ground outside the place and to go out and do work on the land).“It's not about this concept about being free and everything’s wonderful,” continues Bob Lovell. “You need to talk to my father about that; about being barefoot at the age of eleven; sleeping in straw and army blankets under the Vardo with just canvas sheets down the side in a Welsh winter.”

Bob Lovell’s persuasive arguments and discussions may have worked with the organisers of The Gypsy Extravaganza, but “the other lot” - The Original Gypsy Fair – proved to be a tougher nut to crack and this was a nut that became even tougher when the original owners of The Original Gypsy Fair sold their enterprise to a businessman called Jim Banks. Initials attempts by Bob Lovell to negotiate with Jim Banks failed, and eventually Bob Lovell’s campaign was covered by the popular New Zealand Herald newspaper after he contacted them to gain some public support and recognition for what he was trying to achieve.

“The Herald asked me to do an interview and I really got stuck in,” says Bob Lovell. “Then they let Jim Banks reply. And you know what he said? He said, ‘that guy's got big chip on his shoulder’. Since then, we wrote to the Government Ministry of ethnicity, and they replied to us all sympathetic; ‘yes, we understand, Mr. Lovell and blah, blah, blah’. And I said, look, we're not trying to stop these people from their lifestyle, but morally and everything else, them using Gypsy with capital G, this misleading to the New Zealand public because that's not who we are at all,” he explains. “But the big thing about what the Original Gypsy Fair does is that the organisers put up posters promoting their fair with photos of vardos going to Appleby Fair on it. And the two photos they use the most are of the Finney family and the Elliotts, and they even used a photo of Gordon Boswell in one of their posters just before he died and I said to the organisers; ‘you do realize that man is my cousin and he just died. How dare you?’. And you know what they said to us? They said; ‘why don’t you f*ck off’, sighs Bob Lovell. “Over the years I talked to them, but they wouldn't take the name out; I couldn't make them. It would have cost me $10,000 just to get it in the courts with a lawyer, and there was no way I could do it.”

Bob Lovell was also kept busy around the start of the millennium as more and more Roma from eastern European countries began arriving in New Zealand and Australia. “I was contacted by A Roma man calling from Europe somewhere in the middle of the night, it was around the year 2000,” says Bob Lovell. He said ‘is this Bob?’, and I said yes. And he replied, ‘go to Auckland airport tomorrow, where some of our people from the Czech Republic will be arriving and I want you to look after them’.”

Bob Lovell explains that a lot of Roma from eastern Europe where also starting to arrive in Australia at the time, but these where the first arrivals that he knew of that were to arrive in New Zealand. Bob Lovell was at the airport next day and met five extended families who had come to New Zealand from the Czech Republic seeking asylum. At first the authorities would not grant the families refugee status, so Bob Lovell got to work, learning on the job as he fought for those and other Czech Roma families right to remain and the right to not be deported back to a country where they had suffered from some appalling racism and discrimination. “I could speak to the older ones in Romani and we could understand each other because I couldn't speak Czech, of course,” explains Bob Lovell.

Not having done this kind of support work before, Bob Lovell had to learn fast. Engaging a specialist lawyer willing to work for free was the first step, as was persuading his local MP to give support. Bob Lovell also had support from Ronald Lee and Julia Lovell, who were Romany campaigners doing similar work in Canada, and engaging with the Australian TV and print media to raise awareness.

Eventually Bob Lovell managed to get hold of the family’s medical and police records from the Czech Republic alongside photographs of the various scars from the stab wounds and broken bones the Roma men had suffered at the hands of Czech racists – both from the Czech authorities and from the far-right Czech gangs – which were instrumental in proving to the New Zealand authorities that the Roma lives would be in danger if they were sent back. Bob could not save them all however, and some families failed to gain refugee status and were deported back to the Czech Republic.

“There was one really sad case,” says Bob Lovell. “They were a lovely family, and they had two young girls who within months of starting high-school in West Auckland, were doing well and were at the top of their classes. But they got sent back because the father had an artificial leg, but he had lost his leg from an illness and not from a racist attack and the Government said that he would be a burden on the New Zealand welfare system. It was sad. They cried and cried, but I couldn't do any more for them, so they had to go back.”

Whilst a few of the families were deported, most of the families were granted refugee status and most of them then moved to Australia which has a much, much larger Roma community and more work opportunities for newly arrived immigrants than New Zealand. “One of the daughters from one of the families who went to Australia contacted me just before Covid hit saying how they wished to remember me, and to be remembered,” says Bob Lovell. “And they all seem to be doing all right, although of course most of the older people that first arrived have passed on since then, which makes me feel old, really.”

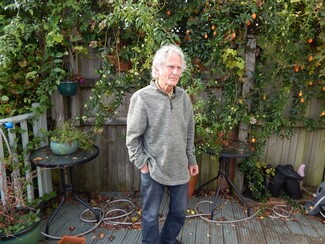

We finish the interview, and we then go inside from Allison’s garden so I can film Bob performing some of his songs, which are as good as you would expect for an award-winning folk singer. The songs make me feel both sad but also cheer me up and fill me with passion at the same time, which is exactly what good folk music should do. Bob tells me that he last played the guitar in 2017, due to “physical stuff” that made it difficult to use his hands, but then when he arrived in Wales four weeks ago, he found he could suddenly play again. “I am a bit shaky,” laughs Bob. I then pack up my gear and Allison’s husband arrives to give me a lift back to Swansea train station. Bob gets in the car with me to see me to the station and we continue talking as we drive. Bob tells me about another passion in his life, which is his love of sailing, and how he builds his own boats. I also find out that Bob had served in Royal New Zealand Navy in the late 1960’s and we chat boats, diesel engines, sails and wood-burners, with Bob telling me about his sailing and the sea, and me telling Bob about my home on a canal narrowboat. “When I get back, I want to build one more sailing boat,” Bob explains, and tells me about what kind of sails it is going to have, what size it will be, and what materials he is going to use to construct it. But that, as they say, is another story.

We arrive at the station. I run to catch my train as Bob is driven back to Allison’s house, where he will then start preparing and packing for his gruelling 19-hour flight the next day, which will take him back home to his life as a Welsh Kale in New Zealand, where his father had been blown, like a leaf on the wind after the Second World War; to a new country on the other side of the world.

Interview and lead photograph by Mike Doherty/Travellers' Times

(All other photographs courtesy of Bob Lovell)