August 2nd: The Roma Holocaust Memorial Day

August 2nd marks The Roma Holocaust Memorial Day. To commemorate the 500,000 to one million lives of the Roma and Sinti killed by Nazi-Occupied Europe, we share this feature that delves into the historical record of that murderous tragedy known by some Roma as the 'O Porrajmos', or 'the devouring'.

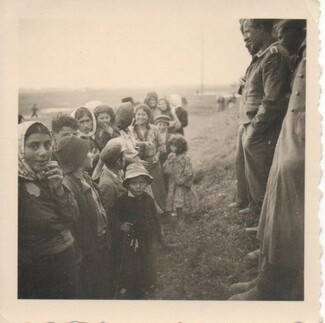

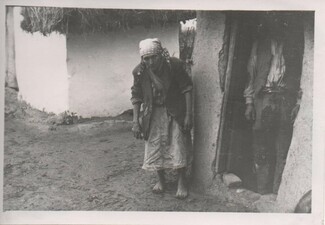

The old photograph shows a soldier in a dusty uniform holding a child with dark skin and dark eyes. The soldier is smiling as the child stares at the camera. The picture has been taken by one of the soldier’s comrades as they rest during an advance into enemy territory. You could be forgiven for imagining that the child will be given some chocolate and then left behind with her family as the advance continues onto the next enemy held village. That may even be what actually happened. Yet the outcome may have been more sinister and the battered fading photograph exudes a certain menace to even the casual observer with no knowledge of military history. To those with more knowledge, the clues are there in the uniform the soldier is wearing. The uniform is a German uniform, the picture is from 1942 and it was taken as the German Wehrmacht swept into the Balkans on its quest to conquer Eastern Europe and impose Hitler's genocidal policies of Aryan racial purity. The child that the photographer’s 'kamerad' is holding is a Roma child. What may have happened to that child can only be pieced together by examining the historical record.

“The Nazis considered the 'Zigeuner', or 'Gypsies', to be a social nuisance that would spoil the pure blood of the Aryan Master-race,” says Ruth Barnett, a Jewish Holocaust survivor rescued from Germany by the British organised 'kindertransport'. She was rescued and brought to England as a child in 1939 and fostered on a Sussex farm and now uses her experience to teach school children about difference and prejudice. Ruth says that the mass murder of between a quarter of a million and one million Roma and Sinti by the National Socialist regime during World War Two has been “airbrushed” from many classic accounts of the Holocaust.

“The Nazi attempt to wipe out all the Jews and Roma in Europe is called 'The Shoah' or 'the burden' by Jews, and 'O Porrajmos', or 'the devouring', by Roma,” says Ruth. “When the Nazis were defeated in 1945 and the camps liberated, the world was horrified to learn how the Jews had been rounded up, brutally treated, exploited as slave labour and murdered in gas chambers. There was hardly a mention of the Sinti and Roma Gypsies who went through the same awful experiences.” Shauna Levin, Director of René Cassin, a Jewish human rights organisation that campaigns on Roma rights and recognition, links this apparent historical amnesia to the present: “Although there are varying estimates about the exact death toll experienced by the Roma community, there is no question that Roma suffering during this time has not received enough attention,” she says. “Germany only officially recognised the Porrajmos in 1982. This is symbolic of the general reluctance to condemn anti-Roma biases that still exists today.”

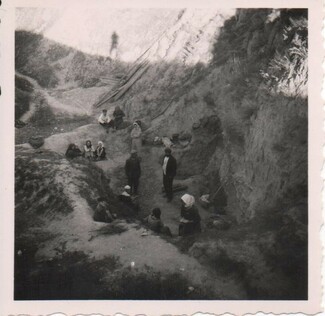

The photograph of the German soldier and the Roma child come from a previously unpublished collection of what Professor Rainer Schulze, an expert on the Nazi 'final solution' and the Roma, describes as “an extremely rare historical record of encounters between German soldiers and Roma populations as the German Army invaded the Caucus and Balkan regions of Eastern Europe.” The collection, never before seen in public, was extracted “for a considerable sum” from the “murky” and “secretive” world of private Holocaust memorabilia collectors by Roma and Gypsy heritage collector Bob Dawson. Unlike the Holocaust memorabilia collectors who keep their collections of objects and photographs under wraps, Bob Dawson has made his collection available to scholars and campaigners. The majority of Bob Dawson's collections are now kept by Reading University and the photographs of the German soldiers with Roma are his most recent acquisition.

“You have to understand that photographs of Gypsies in World War Two are very scarce,” says Bob Dawson. “Jews might be photographed to show them 'getting what they deserved' are so much commoner. Nazi racial theory met a stumbling block with the Roma and Sinti as, because of their ethnic origins in Northern India, they were more 'Aryan' than the Germans and yet the Nazis realised that they were not Aryan in the same way as the Nordic ideal.” Bob Dawson explains that Nazi racial theorists, such as Hans Günther, had to find an explanation to explain “alleged racial flaws” and that the solution was to label Roma and Sinti as 'asocial' and distinct from Germanic Ayrans because of their mingling with “inferior races”. “Gypsyness one generation further back than Jews was fatal under Nazi racial laws,” he says. “Therefore they could be even less fit for photographing than Jews, and of course, there were not as many of them either. If you have a look at some of the collections that are for sale, many have no Gypsy photographs at all, or only occasional ones. Therefore an accumulation like this is very rare indeed.”

Professor Schulze agrees that the photographs are a unique discovery and that up till now there were “only very few” publicly available pictures taken of such normal looking encounters between German soldiers and Roma and Sinti during the rise and fall of Hitler’s Third Reich. Most surviving photos of Roma and Sinti are “official” photographs, explains Professor Schulze, mainly taken during Dr Joseph Mengele's infamous medical experiments on Jewish and Gypsy children at the Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp. “Obviously there would have been more 'unofficial' photographs taken by German soldiers,” he says. “But these have either been lost to the ravages of time or remain in private collections.” Professor Schulze adds that, although the pictures are almost certainly encounters between German soldiers and Roma populations in Southern Eastern Europe, it is impossible to pinpoint exactly when and where they were taken.

“Some of the captioning mentions Croatia,” says Professor Schulze, “some pictures show cattle trucks and some may be work details, deportations or even preludes to massacres, but without clear information from whoever took them, their exact provenance will remain unclear.” Bob Dawson agrees that certainties about the photographs are elusive. He has gleaned what clues he can from the captioning and cataloguing of the photographs and doubts whether the original seller, whom he describes “more as an accumulator than a collector”, would have any more information to give. “Some of the photographs had writing on the back, obviously written by the soldier concerned,” he says. “Others had been taken from albums and the seller had put labels on the back with any information present when they were in the soldier’s album. When there was original information on the back it could be very difficult to decipher and old forms of German were sometimes used.”

The Nazi conquest of the Balkans and southern Eastern Europe began when Hitler ordered the invasion of Yugoslavia, a former ally, in the spring of 1941 after they refused to allow German troops to cross its borders to attack Greece, the last remaining allied power in Western Europe. With Czechoslovakia already conquered, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria and Slovakia joining the Axis powers and the annexation of Yugoslavia, the Nazis were free to implement their genocidal racial policies in southern Eastern Europe – towards both Jewish and Roma populations. State persecution of the German Sinti and European Roma living in Germany had been growing since Hitler took power in 1933. Named as a racial enemy in the 'Protection of Blood and Honour' Nuremberg laws of 1935, German 'Gypsies' were stripped of citizenship and lost their right to vote. Compulsory sterilisation of 'asocial' Gypsies had begun in 1934. In 1938, the first 'Operation Work-shy' took place with many Gypsies being rounded up and forced into municipal labour camps. In 1942, Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, issued the Auschwitz-Erlass declaration and ordered the deportation of “Zigeuner halfbreeds, Rom Zigeuner and members of Zigeuner tribes of Balkan origins with non-German blood” to Auschwitz. 'Pure blood' German Sinti and Gypsies with German blood who has served in the German army where exempt, but these distinctions were often ignored by municipal authorities and police during the round-ups.

How these policies were translated on the ground in the newly established Fascist dominions in southern Eastern Europe depended on the region concerned. In Slovakia, a Nazi puppet state, Roma populations survived in greater numbers than in the German occupied Czechoslovakia. Both Jews and Roma were protected from extermination and deportation by the pro-Fascist government until the country was invaded by the Germans in early 1944 after support for the Nazi regime wavered when it became obvious that the Germans were losing the war against Soviet Russia. After occupation and the installation of a Nazi puppet regime, both Jews and Roma were persecuted and exterminated, with many being deported to Auschwitz. In Romania, a pro-Nazi state, nomadic and sedentary Roma were driven eastwards and left to fend for themselves in open camps in Transnistria (Ukraine) with many dying of starvation and disease. Roma populations in Serbia were at first used as forced labour before the survivors were deported to camps in Germany and Poland as the tide of the war turned. In pro-fascist Croatia, formed after the German invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, mass killings started immediately, with Croatian police and soldiers virtually annihilating the Roma population of around 40-50,000, with those not executed, dying of overwork, starvation and disease in the notorious Jasenovac labour camps. In 1943, 7,000 Jewish and Roma inmates of the Jasenovac system were deported to Auschwitz with the collusion of the German authorities.

In addition to these documented incidents of genocide and persecution there where many 'ad-hoc' massacres and killings as the German army and its allies established control over the Balkan region. Massacres were undertaken by both front line troops and the 'special details', or ‘Einsatzgruppen’, that followed in their wake, whose task it was to ‘purify’ newly conquered territories by killing all perceived as enemies of the new National Socialist order. Many nomadic Roma groups were murdered under the pretext of being spies and Roma populations were also killed in retaliation for partisan acts of sabotage and resistance. It is not known how many Sinti, Roma and Western European Gypsies and Travellers were murdered by the Nazi regime or died from illness and starvation in the camps and the true figure will never be known, but the estimates vary from 200,000 to ½ million.

So the fate of the young girl in the photograph and of the other Roma pictured with German soldiers remains unclear, but the picture is important because of what it symbolises and the emotions it raises when we look at it. This is why Ruth Barnet and Rene Cassin think that images such as Mr Dawson’s photographs are useful for their campaigning work. “We all know that history repeats itself,” says Shauna Leven. “We remember events such as the Holocaust in an effort to try to learn from them.” She explains that today's human rights protections, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights are ultimately products of the world's horror at the events of WWII, and that many Jews, including the French Jew Rene Cassin, were involved in their creation. “In many ways, these events contributed to the development of modern human rights concepts and the laws and institutions that exist to protect them. Minority groups, such as Jewish people and the Roma in Europe and Romany Gypsies and Travellers in the UK may still benefit from these protections.”

A young Roma child today faces an uncertain future with bleak prospects for a life free from discrimination, hatred and bigotry which is rife in both Eastern and Western Europe. Roma remain ghettoised in many European countries, to the extent that they are being walled in to keep them away from the rest of the population in Slovakia, there have been anti Roma race riots and marches in Eastern Europe and in the West, politicians have voiced anti-Roma sentiments as governments have presided over policies aimed at clearing Roma camps and deporting the inhabitants. An industrial pig farm still operates on the former site of the Lety Roma concentration camp in the Czech Republic despite campaigns by Roma groups to have the farm relocated and the site sanctified for remembrance. The Berlin ‘Memorial to the Sinti and Roma Murdered und the National Socialist Regime’ was only finally opened in 2012 after 20 years of campaigning by Roma groups. Europe-wide, Roma, Gypsies and other former nomadic people are still seen as 'asocial' and their very existence is all too often seen as a problem that needs a ‘solution’.

Yet, for many Roma campaigners, remembrance of the Porrajmos is vital to the fight for rights and recognition. On 2nd August 2013, a ceremony of remembrance took place at Krakow, Auschwitz and at the Holocaust Memorial stone in Hyde Park, London. Both events were attended by Roma activists and campaigners. The events were held to mark the night of 2/3 August, the night that the Zigeunerfamilienlager, or 'gypsy family camp', in the Auschwitz concentration and death camp was liquidated and the remaining 2,900 inmates were taken to the gas chambers and their deaths. Professor Schulze was invited to speak at the Hyde Park event. He explained that the Roma and Sinti were unique in that the families were kept together in a single camp: “The fact that it was a family camp is an indicator of Roma self assertion in the hardest of times,” he said. “The Nazis fully well knew that they would have a lot of trouble on their hands if they split the Roma families. So the men were not separated from the women and the children, they were kept in one camp. This, at least for a period of time, left families intact, solidarity intact and a modicum of dignity could be kept by those Sinti and Roma incarcerated in Auschwitz”. Ladislav Balaz, a Roma activist from Roma-Europe, also speaking in Hyde Park, linked the past to events happening today: “We are here to recall the Porrajmos, which must never be forgotten,” he said.

By Mike Doherty