Children forcibly migrated by the state should get compensation - says inquiry into historic abuse

“Defies belief” - theTravellers’ Times investigates whether Gypsy and Traveller children were amongst the tens of thousands of children forcibly migrated by government aided overseas settlement programmes that only ended in 1970.

Children forcibly migrated between 1947 and 1970 by the government should be paid compensation for the abuse and neglect they suffered, says an inquiry – as evidence emerges that Gypsy and Traveller children may have been amongst the children involved both during that period and in the decades before.

Over 4,000 children were taken from their families and sent from the UK, during this period after the Second World War, to countries such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada, says the report by the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse. The report goes on to say that many suffered appalling abuse – including horrific sexual abuse - at many of the the care homes, religious institutions and foster families they were sent to. An estimated 2,000 of those child victims are still alive. Many other children were forcibly migrated in the decades before the Second World War, with the majority – 90,000 - being shipped to Canada.

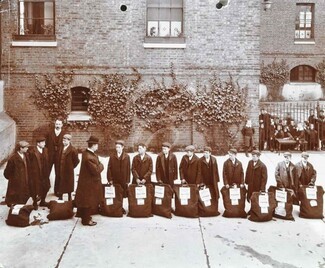

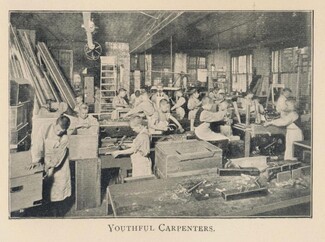

Many of the children were sent to work houses, farms and factories run by ‘voluntary’ organisations who were meant to protect the children and somewhere ‘fostered’ to individual families. Voluntary societies such as Barnardo’s, the Quarrier Homes, the National Children’s Home (NCH), the Church of England Waifs and Strays Society and the Fairbridge Society also became involved, as did the Catholic Church and the Christian Brothers.

Some of those organisations that are still in existence where cross-examined during the 20-day inquiry, alongside surviving victims, and thousands of records are available on the Inquiries website. The Children’s Society were amongst those organisations giving evidence on their historic forced immigration programmes.

“The child migration started at the Children's Society in about 1883. I think four children were sent to Canada at that stage,” they told the Inquiry.

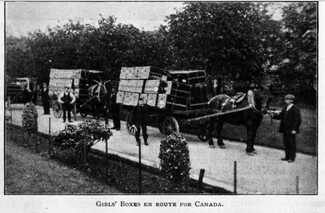

“Then by 1915, 2,250 children had been migrated to Canada to homes which had been founded and were being run by Children's Society in Canada. There was a combination of children being in those (children’s) homes and also being boarded out, sort of fostered to other families, in Canada.”

The Children’s Society also admitted that they sent a further 876 children to Canada between 1920 and 1937.

The Travellers’ Times contacted Doctor Becky Taylor, a social historian at the University of East Anglia, and asked her if she had come across any evidence of forced migration of Traveller children.

Dr Taylor, who wrote a book about the modern social history of the UK’s Travellers, told the Travellers’ Times that “it is not impossible” that Gypsy and Traveller children were included in those forcibly taken and sent abroad, adding that the 1917 Scottish census recorded that nearly 1/5 of Scottish Traveller children had been removed from their families and sent to state institutions because of “non-compliance” with laws on schooling.

“I have come across evidence of Traveller children being sent to Industrial Schools (an early form of reformatory/borstal) if their parents didn't comply with the requirement for children to have 200 attendances at school per year and it was from the Industrial Schools that some of the child migrants were selected. So, nothing direct, but not impossible,” said Dr Taylor.

In Canada, the search for Gypsy children forcibly snatched and sent there during the 1940s to 1960s - and previously - goes on unabated. It’s a heartbreaking story.

Cathay Birch of United Gypsy Roma and Traveller Alliance, who advocates for an inquiry into forced adoption by Social Serves of the United Kingdom, agrees saying, “It is a story that defies belief. Adding, “It seems inconceivable that a British government would order the migration of tens of thousands of its children to far-flung corners of the globe, severing, at a stroke, all connection with family, country and past.”

Reuniting these long-lost families has become an important part of Cathay's work. Even for a genealogist, it’s not an easy task. "I used electoral rolls to help families, but had to be very careful as this could cause a lot of sadness or trouble with those still alive. Most Gypsies are very happy to find a relative though, from stories"

“The ones I have helped were all taken from families in Scotland. There has been no admittance from the UK government and definitely no compensation. They are forgotten stolen children.” According to Canada Children’s Society, they alone sent up to 3,000 children to Canada where they were boarded out in foster homes or kept in establishments run by them. They were one of many organisations that shipped an astonishing 90,000 children to Canada before the Second World War.

After World War Two, the nation’s orphanages were scoured for suitable children and some were also shipped to Canada. “The children were told their parents were dead. In fact, many parents, destitute after the war, were very much alive and believed their children were in temporary care,” says Birch. When families went to reclaim their children from orphanages, they were told they had already been adopted.

The Government of Canada has a massive archive of British Home Children from 1869 to 1932 https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/immigration/immigration-records/home-children-1869-1930/Pages/home-children.aspx. However, a preliminary database search reveals only one Gypsy noted. When searching well known Romany names such as Lovell, Wood and others, many children are revealed on the passenger lists and working on farms throughout Canada.

One such child is Margaret Doyle’s (name is changed) grandmother who was sent in 1930 to Canada through the Catholic society. “It's my belief her family were Irish Gypsy/Traveller”, she said. “They just show up in Islington and I have trouble finding them before that.”

So many loose ends and with good reason. “We would never allow our kids to be adopted. They have to be snatched!” says Birch. “If they were adopted they were no longer treated as Gypsies."

We can thank women like Cathay Birch for keeping hopes alive that one day these children will be found. And she has found many, although for privacy reasons they cannot be named.

The Children’s Society, and many other of the organisations involved, has publically apologised.

“We welcome the publication of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse report on its child migration hearings, which has shone a much needed light on the abuse suffered by children who were sent overseas by charities and other agencies as part of government-backed child migration programmes in the last century,” they said in a statement released during the hearings.

In 2010, Gordon Brown, Prime Minster of the then Labour Government, apologised for the state collusion in forced migration programmes and the abuse of children.

The Travellers’ Times is appealing to our readers to contact us if you think that any of your kith and kin were affected by the forced migration of children programmes both during the period the Inquiry covers and the preceding decades. Please contact travellerstimes@ruralmedia.co.uk by email, send us a message on our Facebook page, or call us on 01432 344 039.

The Truth Project is taking testimony from anyone who has suffered sexual abuse as a child which has been enabled by state or organisational action or inaction.

The Truth Project, which is part of the Inquiry, was set up for victims and survivors of child sexual abuse to share their experiences in a supportive and confidential setting. It’s part of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse.

Find out more at: www.truthproject.org.uk or call 0800 917 1000.

(Main picture: Four children arriving at the Fairbridge farm school, Molong, Australia.)

A brief history of child migration – excerpts from the report into child migration programmes:

Child migration can be traced back to 1618 when poor children were sent to the American colonies as apprentices. Age five was sometimes regarded as a minimum but there are numerous examples of younger children being migrated. Many child migrants were described as ‘orphans’ but did in fact have one or both parents alive.

Over time, particular individuals established specific migration programmes: for example, Captain Brenton set up the Children’s Friend Society sending children to South Africa, and Annie Macpherson and Maria Rye set up a child migration scheme to Canada. Voluntary societies such as Barnardo’s, the Quarrier Homes, the National Children’s Home (NCH), the Church of England Waifs and Strays Society and the Fairbridge Society also became involved, as did the Catholic Church. The rationales for migration varied but in summary they included “humanitarian claims to be rescuing children from poor and unsuitable environments and providing them with new opportunities overseas, imperialist plans to consolidate the white, Anglo-Saxon population in imperial territories, [and] religious concerns with safeguarding children’s Catholic faith or ensuring that a particular denomination was well represented amongst imperial settlers”.

By far the largest number of child migrants, around 90,000, went to Canada from the 1860s.After 1924, children were only migrated to institutional care in Canada, indeed only to the Prince of Wales Farm School in British Columbia where 329 children were sent.

From 1947 to 1965, eight approved organisations migrated a total of 3,170 children to Australia. The peak years for child migration to Australia were 1947 and 1950 to 1955. Around 400 children in total were sent by local authorities, a small percentage of the total number of children in local authority care. Post-War child migration to Southern Rhodesia involved 276 children being sent to the Rhodesia Fairbridge Memorial College.

As the UK economy improved from the 1950s, fewer children came into the voluntary societies’ care. The experts’ understanding was that Australian child migration ended “when the remaining voluntary childcare societies could no longer recruit children to send or no longer wished to do so. Very likely, due to changes in welfare support for families, more children in need were being contained and supported in their natural families or were being fostered or adopted, and the number of children needing anything but temporary institutional care diminished”. The last child was migrated to Australia in 1970. Most if not all of those children who had been migrated remained within their receiving institution, despite the concerns that had been raised about the appalling conditions in which many of them were accommodated.

Many, but not all, of the institutions involved in child migration have apologised for their role in it, some more fulsomely than others, and some for the first time in evidence before us. Witnesses told us of their experiences of brutalising regimes that involved physical and sexual abuse, poor living conditions, poor health care, and poor medical and educational provision. It is important, when considering the incidents of child sexual abuse, that we appreciate the full range of appalling conditions in which these children lived. This broader context of their lives is included in this report.

By Mike Doherty and Frances Roberts-Reilly/TT News